Of the roughly 15,000 British and US aircraft delivered to the Soviet Union during World War II, P-39s, P-40s, Hurricanes and A-20s chief among them, twelve of a lesser-known British type, the Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle, were ferried to Moscow in the middle of 1943. Though numerically insignificant, the Albemarle detachment offers a useful case study in the practical and diplomatic complexities of Lend-Lease cooperation. The aircraft’s mixed construction, unusual systems, and non-standard logistics requirements exposed the limits of Soviet-British interoperability, and its short, uneven service life illustrates how even minor equipment transfers could reveal deeper differences in doctrine, infrastructure, and technical culture.

Background: A Transport the RAF Did Not Want

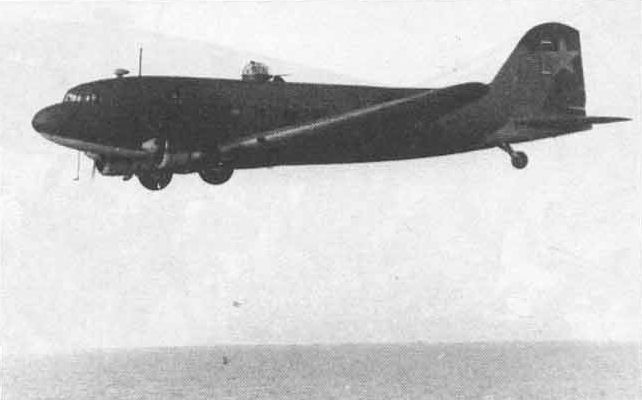

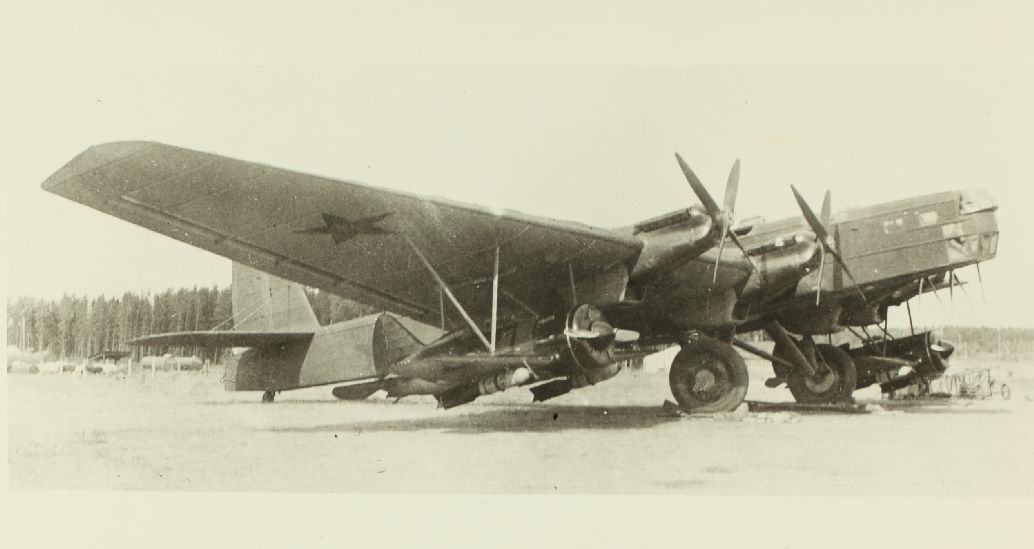

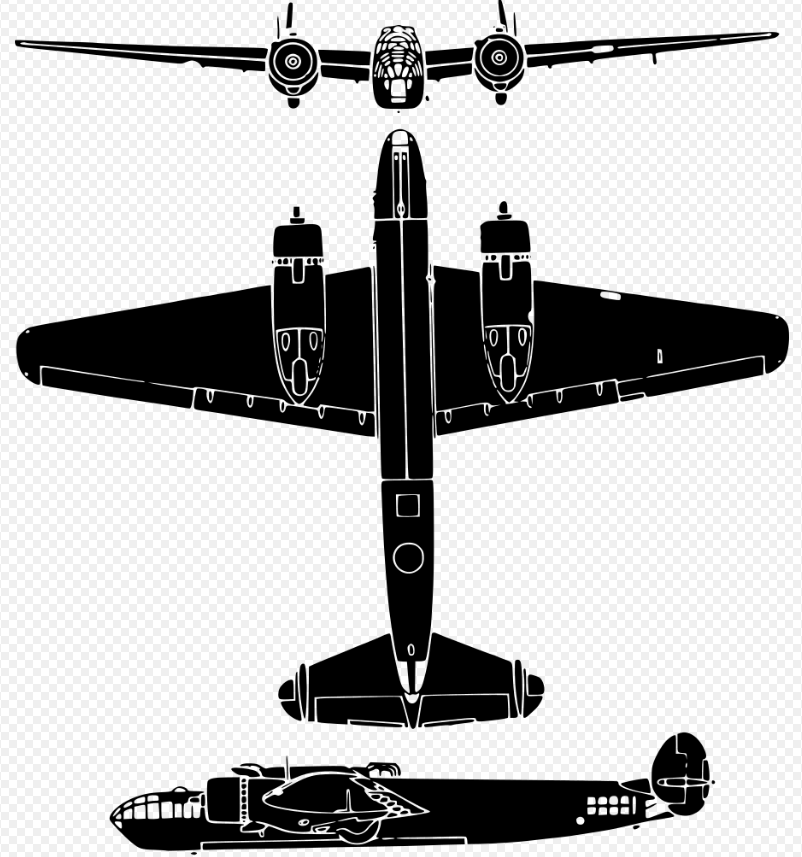

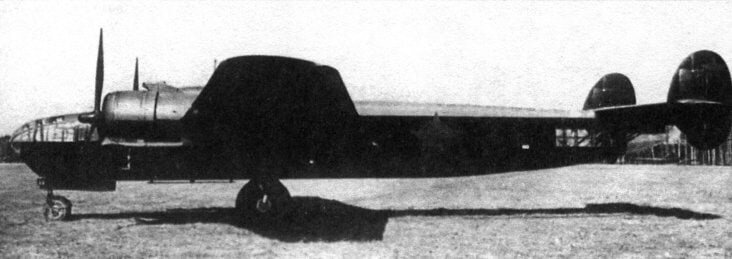

Originally developed to serve as a medium bomber that could be mass-produced without the use of light alloys so that manufacturers from outside the aviation industry could produce it in subsections, the Albemarle was relegated to general reconnaissance and transport duties almost immediately after being accepted by the RAF. Though initial designs envisioned the bomber being powered by two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, Bristol Hercules XI 14-cylinder air-cooled radial engines were ultimately used and the aircrafts weight ballooned to more than 28,000 pounds. Consequently, when the RAF began to accept deliveries of the type, it was determined that the Vickers Wellington was far more adept as a medium bomber, and the Albemarle would therefore be reoriented towards reconnaissance and transport roles.

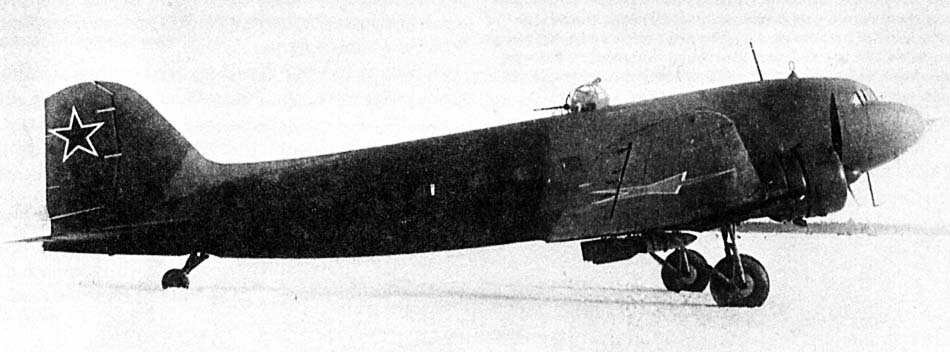

In the summer of 1942, the Soviet ambassador in London inquired about the possibility of the RAF providing the VVS with transport aircraft. In September, the British agreed to provide their Soviet allies with Albemarles that had been modified to serve as transports. With its modern two-engine monoplane design, air-cooled engines, and sectional construction, which was deemed to provide ease of maintenance, the Albemarle, at first glance, looked appealing to Soviet delegates. However, on closer inspection, several glaring issues became apparent that would make the type’s operation on the Eastern Front complicated. For one, the Hercules required 100-octane fuel, which the USSR produced only in limited quantities and primarily relied on Lend-Lease shipments to obtain, creating an immediate logistical burden. Another problem was the hydraulically operated tricycle landing gear which, though more modern than typical Soviet transports, was mechanically complex and sensitive to the rough, uneven airfield surfaces common in the theater, limiting its practicality as a transport. Furthermore, having been designed as a bomber, the aircraft lacked a loading hatch and couldn’t carry oversized cargo.

The British, in turn, recommended several modifications, most notably removing one of the fuselage fuel tanks, turret and armor to provide more cargo space as well as cutting a side hitch to allow for loading and unloading. Though the VVS had major concerns about the modifications, specifically the decrease in the aircraft’s range and the removal of defensive capabilities, the Soviet representatives agreed to the proposed modifications, and submitted a request for 100 aircraft, with 25 being delivered as soon as possible.

Negotiation and Preparation for Transfer

In December 1942, the State Defence Committee (GKO) issued a decree creating the 1st Air Transport Division, which was tasked with ferrying aircraft from Scotland to Moscow. The following month, Soviet crews were dispatched to fly the route, much of which lay over German-held territory. The ferries were to depart from RAF Errol in Scotland, fly over the North Sea, occupied Denmark, neutral Sweden, the German-held Baltic States, and then down to Vnukovo in Moscow. The 9.5-hour flight was scheduled at night and high altitude, necessitating minor modifications to the engines’ oil systems. Initially, nine crews were sent to train in Scotland and eleven were to train in Moscow, but this was abandoned and all crews ended up training in the UK. To familiarize themselves with take-offs and landings using a tricycle nose gear, the crews first flew Douglas A‑20 Havocs (Bostons) before transitioning to the Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle.

In his report from the Soviet military mission in Britain, Admiral Nikolai Kharlamov noted:

“The flight personnel began work according to program: pilots and flight-mechanics are studying the aircraft, engine and equipment at factories; radio-operators and navigators are studying the technical component at Errol. On 20 January flying training will begin. The crews are accommodated at Errol satisfactorily and are adequately supplied with food. A shortcoming is the appearance of the pilots arriving in mismatched uniforms, without insignia. This has complicated relations between them and the British instructors (officers), who regard the pilots as enlisted personnel.”

The language barrier between British and Soviet crews proved to be problematic, with a single RAF instructor—Jan Taudy, a Czech by nationality who had spent time in the Soviet Union—available to provide translation. There were, in addition, issues with the ranking system. The Soviet mechanics deployed to Scotland held a rank equivalent to Lieutenant, and British standards dictated that those with officer rank delegate and supervise actual maintenance work. Consequently, in what could pass for a scene out of Monty Python, Russian-speaking officers were expected to guide and supervise English-speaking RAF mechanics with no translators.

The British had, at first, committed to providing 15 aircraft per month, but it soon became clear that this production target could not be met. What is more, some of the aircraft were rejected by Soviet due to various defects, with one anonymous NKGB (secret police) staff member reporting, “The British delay aircraft acceptance on purpose… the Soviet engineers are not allowed to maintain the aircraft.”

The Ferry Flights to Moscow

After a four-week delay, the first aircraft departed RAF Errol on March 3, 1943 and, despite poor weather and significant ice accretion on the airframe, arrived at Vnukovo without incident. As General-Colonel of Aviation Fyodor Astakhov, head of the Main Directorate of the Civil Air Fleet, reported to GKO deputy chairman Vyacheslav Molotov:

“I report that on the night of 3–4 March the first Albemarle aircraft, piloted by Shornikov, completed the flight from England to the USSR. It departed from Errol Airfield on 3 March at 20:45 Moscow time and landed safely at Vnukovo at 08:00 on 4 March. Flight duration was 11 hours 15 minutes. Altitude 4–4.5 km. The aircraft covered a distance of 2,662 km.”

The following week, three additional Albemarles departed Errol in staggered intervals. One of these, piloted by Captain A. I. Kulikov, lost contact approximately 200 miles off the Scottish coast and was never heard from again.

On another aircraft, piloted by Captain Kachanov, severe icing caused the Albemarle to enter an uncontrolled descent. Kachanov managed to level the aircraft at the last moment, only to find it flying at low altitude directly over German positions, which immediately opened fire. He escaped back into the cloud layer, but the turbulence had snapped off all radio antennas, forcing the crew to navigate eastward solely by compass. After several hours, the weather cleared and the crew identified the Volga River below. When the Albemarle finally approached Arskoe Pole airfield at Kazan, local anti-aircraft gunners, unaware of the aircraft’s identity, opened fire. Fortunately, the aircraft sustained only minor damage and no crew members were injured.

Between 3 March and the end of April, Soviet crews ferried fourteen aircraft from RAF Errol to Vnukovo, of which only twelve reached Soviet territory. In addition to Captain Kulikov’s aircraft, which disappeared over the North Sea, another Albemarle piloted by Lieutenant F. F. Ilchenko was lost near Sweden. Initial reports suggested the aircraft had been shot down by Swedish anti-aircraft fire, but later assessments concluded that it was more likely intercepted and destroyed by German fighters. In any case, Ilchenko and his crew were never heard from again.Of the twelve Albemarles that arrived in the Soviet Union, no two shared an identical configuration. Armament varied widely, with some aircraft carrying no defensive weapons at all. Fuel systems differed as well, with several airframes carrying three tanks and others fitted with four. Some examples were equipped with flame dampers, and others were configured for glider towing. One of the twelve lacked a cargo door altogether.

Throughout the course of April, as the days became longer and the nights became shorter, concern increased over the chosen ferry route. As General-Colonel of Aviation Fyodor Astakhov reported to Molotov, Mikoyan, and Malenkov:

“Beginning on 1 May, there will not be enough darkness for ferry flights. The route lies near the latitude of the white nights, and our aircraft can be easily detected by enemy fighters. I consider it necessary to revise the ferrying route in order to preserve flight personnel and equipment. We propose for your consideration a southern route, to be used during the short-night period until 1 September, through Algiers, Tripoli, Cairo, Tehran, and Baku. Total distance 10,075 kilometers. We request permission to begin negotiations with the British to clarify airfields for intermediate landings and to arrange technical support.”

After deliberations, London agreed to the new route. The aircraft were to be ferried from RAF Hurn to Moscow via Casablanca, Tripoli, Cairo, Tehran, Baku, and Stalingrad.

Enjoying this?

My best narrative history writing goes to Substack. Check it out here.

Technical Evaluation in the USSR

Meanwhile, evaluations of the Albemarle had begun at both NII GVF, the Scientific Research Institute of the Civil Air Fleet, and NII VVS, the Scientific Research Institute of the Air Force. NII GVF was assigned the task of developing a standardized armament installation for the transports using Soviet-built machine guns. NII VVS conducted an extensive flight-test program, completing forty-eight individual sorties with a total flying time of twenty-seven hours. For comparison, the Albemarle’s performance was measured against that of the Soviet-built Il-4 and Er-2, as well as the North American B-25C. The AW.41 was found to be inferior in speed, ceiling, and rate of climb, although its takeoff and landing characteristics were considered better than those of the Er-2 and B-25. The only consistently positive assessment concerned the power and reliability of the Hercules engines, but this was not enough to offset what testers regarded as serious structural and production shortcomings.

NII GVF, meanwhile, had determined that the aircraft’s high lifting capacity could be useful for compact heavy cargo, but its small loading hatch made the loading and unloading of cargo problematic. Its use as a personnel transport was also evaluated. The cabin could accommodate up to 19 passengers, but in such a configuration, each would have less than half the space of the Lisunov Li-2, the Soviet license-built variant of the DC-3. NII GVF also discovered a new problem: none of the Soviet-produced oils were compatible with the Hercules engines, and special oil containing tributyl phosphate would need to be imported. The fact that its landing gear necessitated the use of long and well-kept runways was also deemed problematic, as such airstrips were rare in front-line operations. The final NII GVF concluded that, “further purchase of the Albemarle-1 aircraft would be impractical. Operation of the aircraft that have already been purchased could be allowed in a cargo variation, and only after the elimination of all detected drawbacks.”

Pilots provided their own evaluations:

“In its flight characteristics, the Albemarle does not belong to the number of modern technical innovations in aircraft construction, but rather to the number of obsolete aircraft being withdrawn from service. As a Soviet pilot, I unfortunately cannot give a positive evaluation.”

As a last resort, the Soviet Navy evaluated the Albemarle for potential use as a torpedo bomber. Although initial assessments suggested that the aircraft might handle such a configuration adequately, it would have required extensive structural and systems modifications. Combined with the existing logistical problems related to incompatible lubricants and high-octane fuel, these factors led the Navy to reject the Albemarle for naval service.

Service in the 1st Air Transport Division

Soviet airmen of the 1st Air Transport Division, meanwhile, had been waiting for additional AW41s to ferry for months. The frustration and boredom of this prolonged inactivity were captured in an undelivered letter written by one of the pilots:

“Dmitry Stepanovich, Anatoly Ivanovich, my friends. It is now almost a year since I left my country, and only three or four months of that time have had any purpose. The rest has been like a ‘London fog’—no goal, no clarity, no sense of what lies ahead. People at home are living through a decisive and intense period of the war, while we, fifty men in a closed circle, nourish ourselves only on radio reports. I can tell you that the full gravity of the situation and the moral strain cannot be understood secondhand. What is happening? This is the question that follows me to sleep at one or two in the morning and greets me again at seven.”

In total, twelve Albemarles were delivered to the Soviet Union and assigned to the 2nd Air Squadron of the 3rd Air Regiment of the 1st Transport Air Division at Vnukovo. Once received, the aircraft were employed on several major cargo routes, including Moscow, Kazan, Kuibyshev, and Aktyubinsk, all of which had long, well-maintained runways suitable for the type. In practice, however, almost every flight was accompanied by mechanical problems, ranging from hydraulic failures to malfunctioning air compressors and propeller pitch-control issues. The aircraft were also stored outdoors at Vnukovo, where prolonged exposure caused the plywood skin to absorb moisture and crack. Among the various nicknames coined by Soviet crews, the most common was Abormot, a play on obormot, meaning “blockhead.”

The various defects and the Albemarle’s general unsuitability for Soviet conditions inevitably led to accidents. On 29 April 1943, one Albemarle crashed on the Moscow–Novosibirsk route; the crew evacuated and survived. Two days later, another AW41 was forced to make a crash landing after an engine failure. The crew again survived, but the aircraft was severely damaged and written off. Additional forced landings followed in Baku, Astrakhan, and Tbilisi, all within the span of several months. By September, the regiment had nine Albemarles remaining, of which only six were serviceable. As a result of the high accident rate, all Soviet operations with the Albemarle were suspended.

Cancellation and Final Disposition

In September, the Soviet chargé d’affaires in London submitted a list of forty identified defects in the Albemarle to Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden. The British, having neither the resources nor the inclination to undertake major design changes to the AW41, rejected the proposal. By this time, deliveries of US-built C-47 transports via the ALSIB route had fully met the VVS requirement for transport aircraft, making further pursuit of the Albemarle unnecessary. By early 1944, the remaining Soviet personnel at RAF Errol had been sent home. In April, the Soviet Union rejected the reaming 86 Albemarles, and the aircraft which had already been accepted, but not ferried, were handed back to the RAF.

The six serviceable aircraft remaining with the 1st Air Transport Division were transferred to the Soviet Navy, where they were briefly employed as transports by the 65th Special Purpose Air Regiment. By mid-1944, all remaining airworthy Albemarles had been reassigned to naval aviation schools for navigator training. At the end of the war, two aircraft were still on the roster, but both were soon written off.

The Albemarle’s brief service in the Soviet Union was small in scale but revealing in substance. It showed how even a minor Lend Lease transfer could expose deeper limits in Allied cooperation. The aircraft was designed for British industrial conditions and British operational needs, and once placed in the very different environment of the Soviet air transport system its shortcomings became impossible to ignore. Every stage of the program, from ferrying to maintenance to frontline use, highlighted practical incompatibilities in logistics, infrastructure and technical practice.

For the VVS, the Albemarle offered neither the performance expected of a combat aircraft nor the reliability needed of a transport. For the British, modifying the type to suit Soviet requirements was neither feasible nor worthwhile. The result was a short service life that ended quietly once better suited American transports became available.

In the end, the Albemarle proved to be an aircraft out of place. It demanded fuel, oils and runways the Soviet Union could not spare, and it delivered performance that did not justify the effort. Once reliable American transports arrived, its brief Soviet career came to a close. The episode stands as a reminder that not all Lend Lease transfers succeeded and that even well-intentioned cooperation could be undone by technical and operational mismatch.

-Patrick Kinville

Did you enjoy this?

My best narrative history writing goes to Substack. Check it out here.

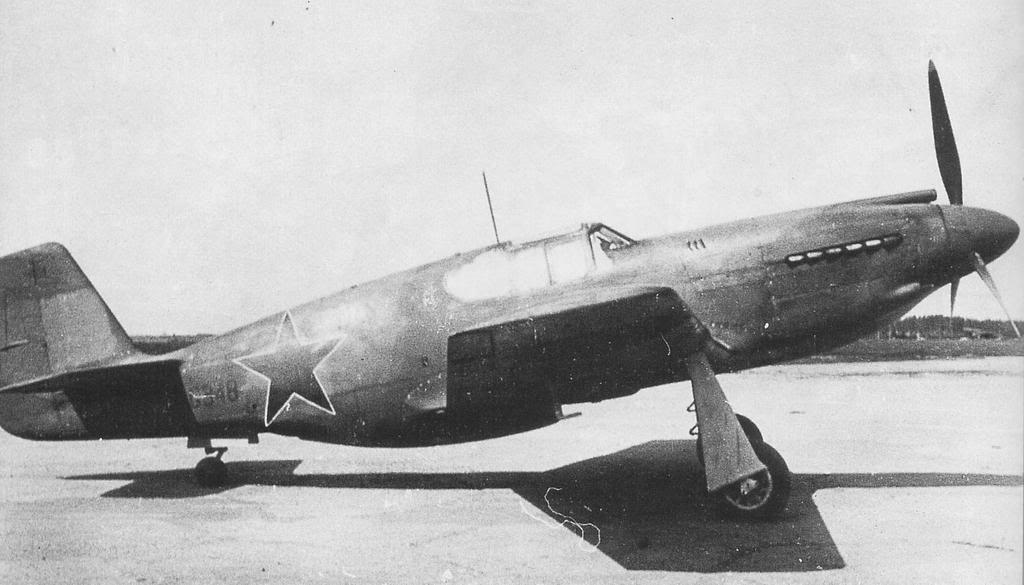

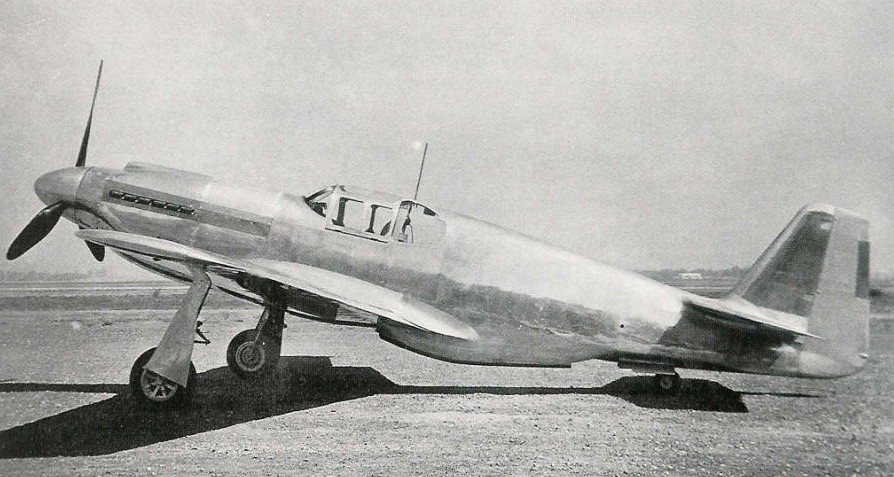

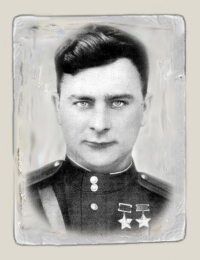

After graduation, Glinka was assigned to the Transcaucasian Military District’s Air Force Fighter Wing near the city of Baku in the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic. In the summer of 1941, in the wake of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, Glinka was assigned to the 45th IAP, which was stationed in Iran during the Anglo-Soviet invasion of the country in August and September. Equipped with a Polikarpov I-16, Glinka did not fly any combat missions during the invasion, but did manage to fly several hundred sorties in the “Rata” before the 45th IAP was transferred to the Crimean Front in early 1942.

After graduation, Glinka was assigned to the Transcaucasian Military District’s Air Force Fighter Wing near the city of Baku in the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic. In the summer of 1941, in the wake of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, Glinka was assigned to the 45th IAP, which was stationed in Iran during the Anglo-Soviet invasion of the country in August and September. Equipped with a Polikarpov I-16, Glinka did not fly any combat missions during the invasion, but did manage to fly several hundred sorties in the “Rata” before the 45th IAP was transferred to the Crimean Front in early 1942.

The 100th GIAP then received a much deserved 6-month rest in late 1943 and early 1944. In the spring of 1944, the regiment was sent to provide air cover the Second and Third Ukrainian Fronts for the Jassy–Kishinev Offensives. In the first week of May, Glinka had yet another brush with death when a Li-2 transport aircraft on which he was traveling crashed into a mountain. Sustaining serious injuries in the crash, Glinka lay in the wreckage for two days before being rescued. In July, after spending two months in the hospital, Glinka rejoined his regiment, which had been sent to provide air cover for the Lvov–Sandomierz Offensive. During the operation, the Soviet ace shot down nine German planes, raising his score to 46. Glinka was inactive until the Battle of Berlin the following spring, where he shot down two Bf-109s and two Fw-190s.

The 100th GIAP then received a much deserved 6-month rest in late 1943 and early 1944. In the spring of 1944, the regiment was sent to provide air cover the Second and Third Ukrainian Fronts for the Jassy–Kishinev Offensives. In the first week of May, Glinka had yet another brush with death when a Li-2 transport aircraft on which he was traveling crashed into a mountain. Sustaining serious injuries in the crash, Glinka lay in the wreckage for two days before being rescued. In July, after spending two months in the hospital, Glinka rejoined his regiment, which had been sent to provide air cover for the Lvov–Sandomierz Offensive. During the operation, the Soviet ace shot down nine German planes, raising his score to 46. Glinka was inactive until the Battle of Berlin the following spring, where he shot down two Bf-109s and two Fw-190s.

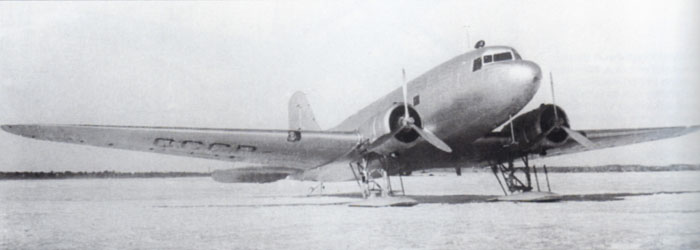

Though Soviet engineers initially hoped to incorporate as few changes as possible to thedesign of the DC-3, by the time the first aircraft made with imported parts rolled out of factory no.84 in November of 1938, almost 1,300 engineering changes had been made to the original Douglas drawings. In addition to converting the measurements from the imperial to the metric system, no small task on its own, numerous modifications had to be executed in order for the aircraft to be able to house the Soviet-built Shvetsov ASh-62 engines, which were a development of the Wright R-1820 Cyclone that had initially been built in the Soviet Union under licence as the Shvetsov M-25. Nevertheless, after a series of trials and errors, the new aircraft passed government tests in 1939, and was designated PS-84 (Passazhirskiy Samolyot 84, or passenger aircraft 84).

Though Soviet engineers initially hoped to incorporate as few changes as possible to thedesign of the DC-3, by the time the first aircraft made with imported parts rolled out of factory no.84 in November of 1938, almost 1,300 engineering changes had been made to the original Douglas drawings. In addition to converting the measurements from the imperial to the metric system, no small task on its own, numerous modifications had to be executed in order for the aircraft to be able to house the Soviet-built Shvetsov ASh-62 engines, which were a development of the Wright R-1820 Cyclone that had initially been built in the Soviet Union under licence as the Shvetsov M-25. Nevertheless, after a series of trials and errors, the new aircraft passed government tests in 1939, and was designated PS-84 (Passazhirskiy Samolyot 84, or passenger aircraft 84).