Long before the era of the B-17, Lancaster, or Heinkel He 177, the Russian Empire fielded a bomber that fundamentally redefined what an aircraft could be. The Ilya Muromets, designed by Igor Sikorsky and first flown in 1913–14, was the first four-engine bomber in history, and the first aircraft conceived from the outset for long-range, heavy-load bombing missions. While contemporary aircraft in Europe were limited to short-range reconnaissance and modest payloads, the Muromets was an ambitious leap ahead: a multi-crew, heavily armed, high-endurance platform that could strike deep behind enemy lines.

Its influence would reverberate for decades. The innovations introduced on the Ilya Muromets—ranging from integrated bomb bays to defensive gun positions and in-flight engine serviceability—anticipated many of the design elements that would become standard in Second World War strategic bombers. Though built in relatively small numbers, and limited by the industrial capacity of Imperial and early Soviet Russia, the Muromets flew hundreds of combat sorties, helped establish the first true bomber squadron in history, and demonstrated that the age of strategic airpower had begun.

This post explores the origin, evolution, and operational legacy of the Ilya Muromets, from its roots as a flying salon for the Tsarist elite to its role in pioneering multi-engine bombing doctrine during World War I and the Russian Civil War. The story begins not with bombs, but with ambition: the idea that the sky could carry not just observers, but an entire coordinated crew, armed and purposeful, over vast distances

Precursor to a Bomber: The Grand and Its Lessons

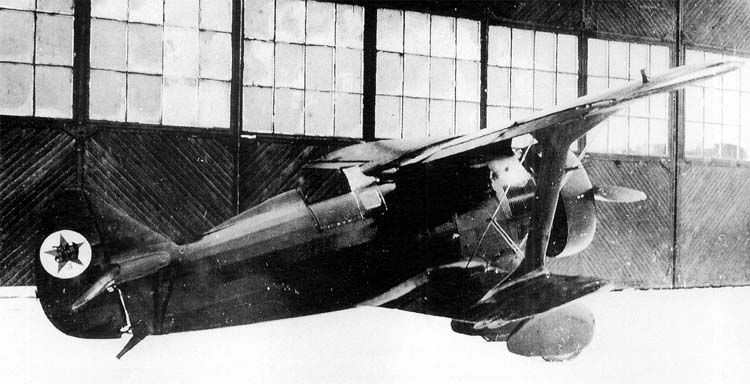

In 1912, Igor Sikorsky, chief engineer at the Russo-Baltic Wagon Works (RBVZ), began developing what would become the world’s first successful four-engine aircraft. Designated the S-21 and informally known as The Grand, it was conceived as a long-range luxury airliner. At a time when even two-engine aircraft posed major aerodynamic and structural challenges, Sikorsky’s design broke new ground. It featured in-flight engine access, an enclosed cockpit with dual controls, and structural endurance suitable for extended operations.

Initial flights in early 1913 used two Argus engines, but the aircraft soon flew with four in a tandem push-pull layout. With a wingspan of over 27 meters and a maximum loaded weight above 4,000 kilograms, The Grand, also known as the Russky Vityaz and Bolshoi Baltisky, proved that large, multi-engine aircraft could be stable and controllable. Public interest surged after its successful flight on May 13, 1913, though its career was cut short by an accident later that summer. Sikorsky used the lessons learned to develop a new design with increased lift capacity, improved crew coordination, and greater combat potential.

From Salon to Strategy: The Birth of the S-22

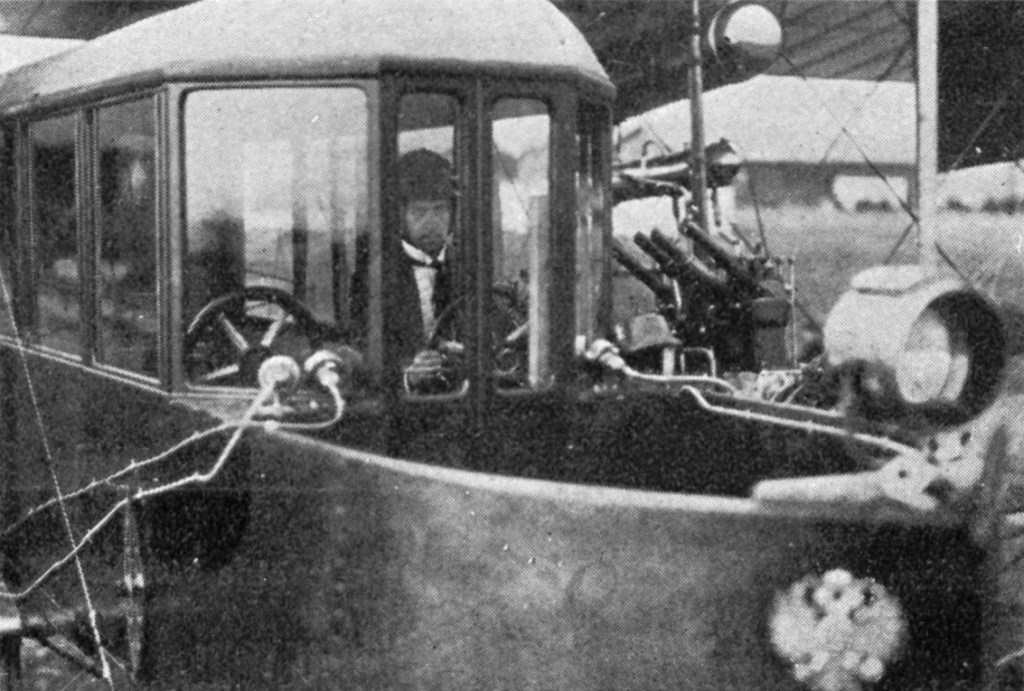

Sikorsky’s follow-up, the S-22, retained the core architecture of The Grand but expanded it into a more refined platform. Still intended as a civilian aircraft, it featured a fully enclosed and insulated cabin with upholstered seating, electric lighting, heating, a lavatory, and even a sleeping berth. It was the first aircraft to integrate the cockpit fully within the fuselage, streamlining both aerodynamics and crew workflow.

The aircraft used four Argus engines mounted in a tractor configuration along the leading edge of the lower wing. Engine nacelles were spaced well outboard of the fuselage and included access panels for in-flight maintenance. Structurally, the fuselage was a timber box reinforced with wire bracing, extending into twin tail booms that supported a cruciform tail. With a wingspan over 30 meters and a takeoff weight exceeding 4,600 kilograms, the S-22 had unmatched range and payload for its time.

By early 1914, military observers began attending test flights. The aircraft’s endurance, redundancy, and crew accommodations suggested broader applications. In the context of rising international tension and the limitations of existing reconnaissance aircraft, Russia’s General Staff began evaluating the S-22 for military service. A demonstration flight with officers aboard proved decisive. Sikorsky was tasked with adapting the aircraft for combat, and ten were ordered in a revised configuration. The platform was formally renamed Ilya Muromets, invoking the legendary Russian folk hero.

Entering Service: The Ilya Muromets at War

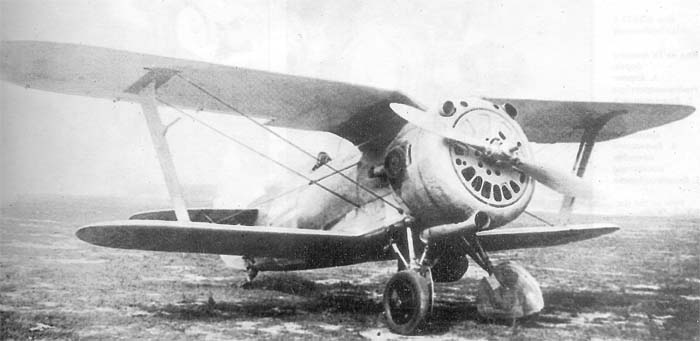

At the start of the First World War, the Imperial Russian Air Service had two operational Ilya Muromets aircraft. Wartime conditions made expansion difficult. The originally planned German Argus engines were no longer available. Only aircraft No. 135 retained them; subsequent airframes used French Salmson engines, including the 14-cylinder 2M7 (200 hp) and the 9-cylinder M9 (130 hp). These were mounted asymmetrically to balance thrust and maintain yaw stability.

On August 14, 1914, the Ministry of War approved the organizational structure for Muromets crews. Each aircraft carried four officers (including a commander and artillery officer), one administrative official, and forty enlisted personnel. Armament included a 37 mm Hotchkiss cannon for anti-Zeppelin use, two Maxim machine guns, two Madsen light machine guns, and two Mauser pistols. The Hotchkiss cannon, with 500 rounds, reflected the strategic role envisioned for the aircraft early on.

Operational experience with the A- and B-series Ilya Muromets aircraft exposed several shortcomings rooted in their civilian design heritage. The large passenger compartments, numerous side windows, and interior fittings intended for comfort contributed excessive weight and aerodynamic drag. Additional fuel tanks and structural reinforcements (added to extend range) further degraded performance. In response, aircraft No. 137 (Muromets III) received significant modifications in November 1914. The forward artillery platform was removed and replaced with a detachable nose mount for a machine gun, and auxiliary fuel tanks were eliminated to reduce structural weight and improve climb rate.

Aircraft No. 143, completed in October 1914, marked the end of the B-series and the transition toward a more militarized airframe. In response to frontline feedback, Sikorsky initiated development of a new variant specifically designed for combat.

Redesign for War: The “Lightened Combat” Muromets

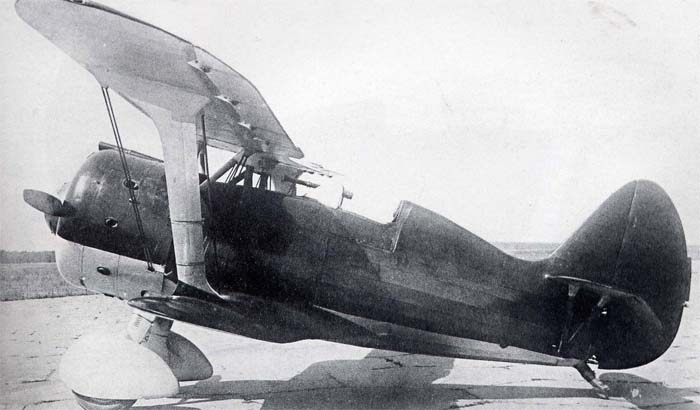

By the autumn of 1914, field reports had made clear that the Ilya Muromets required fundamental revision if it were to serve effectively in a sustained combat role. The next iteration, known informally as the “lightened combat” model, incorporated significant aerodynamic and structural changes. Aircraft Nos. 149, 150, and 151 formed the first production run of this configuration.

The fuselage was shortened by nearly two meters and narrowed to reduce surface area and overall drag. The wingspan was trimmed by approximately three meters. The nose section was reshaped to improve both forward visibility and aerodynamic efficiency. Superfluous features from the aircraft’s civilian origins, most notably excess windows, were eliminated. Internally, the cabin layout was reconfigured to accommodate gunners, observers, and a dedicated bombardier. Most significantly, an enclosed bomb bay was added, enabling ordnance to be released directly from within the fuselage. This represented one of the earliest examples of a fully integrated bomb delivery system, a departure from the improvised release mechanisms used by most contemporary aircraft.

These modifications were more than technical; they reflected a broader doctrinal shift. The Ilya Muromets was no longer treated as a large reconnaissance platform or a passenger aircraft adapted for bombing. It had evolved into a purpose-designed strategic bomber—one capable of carrying a full crew, delivering substantial payloads over operational distances, and returning intact through defensive firepower and structural redundancy.

Refinements to the platform continued throughout the war. In the autumn of 1916, two new variants entered service: the E model and the G model. Of these, the E was especially notable as the largest aircraft produced in the world at the time. It was equipped with four Renault engines, each generating 220 horsepower, a significant upgrade over the 160 horsepower output of the earlier Salmson-powered variants. These engines improved both climb rate and reliability, extending the Muromets‘ operational viability into the final phases of the war.

Into Combat: Operational History of the Ilya Muromets

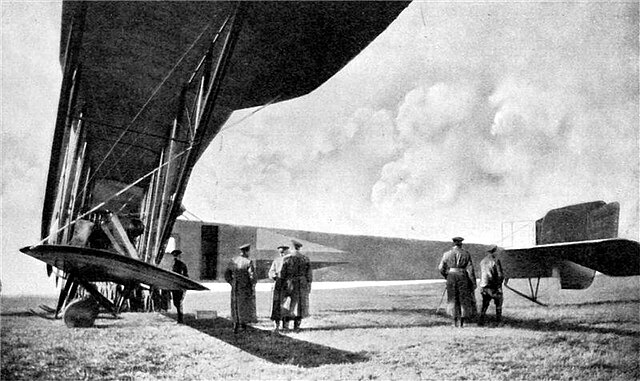

In late 1914, following the redesign of the airframe, the Imperial Russian Air Service began forming the world’s first dedicated heavy bomber unit: the Eskadra Vozdushnykh Korablei (EVK), or Squadron of Flying Ships. Officially established in December, the EVK initially fielded four Ilya Muromets aircraft and was headquartered near Warsaw.

The squadron’s first operational sortie took place in February 1915, targeting German railway infrastructure near Mlawa. Thereafter, the EVK launched a sustained campaign of strategic bombing along the Eastern Front, striking troop concentrations, supply depots, and rail hubs. Missions were typically flown at altitudes between 1,500 and 3,000 meters, safely above the range of most rifle fire and early anti-aircraft guns.

Between 1915 and 1917, the Ilya Muromets fleet flew over 400 sorties, delivering bomb loads that increased from approximately 300–400 kilograms to nearly 800 kilograms as engine performance and structural refinements progressed. The aircraft were also used for reconnaissance, aerial photography, and psychological operations, including leaflet drops and low passes over enemy positions.

Defensive armament evolved to counter the growing German fighter threat. By mid-1915, newer variants carried as many as seven machine guns, with crew stations in the nose, fuselage waist, and tail sections. The combination of altitude, firepower, and crew coordination made the Muromets one of the most survivable aircraft of the war. Only one was confirmed lost to enemy fighters during its entire operational life.

In his memoirs, Igor Sikorsky described a dramatic incident that highlighted the aircraft’s defensive capability:

“On April 25, 1917, the ship ‘Ilia Mourometz XV,’ under the command of Captain Klembovsky, while returning from a bombing raid, was attacked by a group of three pursuit planes. The ship opened fire from its four machine guns. Soon afterward one of the pursuits was hit, fell and crashed in the woods. A few minutes later a second pursuit plane was hit and dropped down. After that the attack was discontinued and the third pursuit plane turned away. The ship was slightly damaged by bullets and one man of the crew was wounded.”

Typical crews included five to seven personnel: pilot, navigator, bombardier, mechanic, and several gunners. Flights often lasted several hours, and crews operated under difficult navigational conditions with only rudimentary instruments and limited radio equipment. Despite these limitations, the Ilya Muromets demonstrated the viability of multi-crew strategic bombing, a concept that would become central to military aviation in the decades to follow.

However, maintaining the aircraft in field conditions proved challenging. The engines required meticulous servicing, and the EVK’s ground crews lacked adequate training. One staff captain, Pankratyev, expressed frustration in a wartime report:

“The unpredictable operation of the ‘Muromets’ at the war front puts its crews in very difficult conditions, which could lead to accusations of lack of activity and unwillingness to work… When the entire army is striving with all its might to fulfill its duty, the ‘Muromets’ crews, during periods of aircraft failure, are doomed to inactivity, which, of course, is unacceptable.”

To improve operational reliability, Pankratyev proposed a solution:

“It would be desirable to supply the ‘Muromets’ crews with two ‘Voisin’-type aircraft. This would allow the unit to continuously carry out its assigned tasks, fulfilling them either with the ‘Muromets’ or the ‘Voisin,’ depending on the circumstances.”

Despite these obstacles and its limited production—only about sixty units were built—the Ilya Muromets had an outsized operational impact. In an era dominated by light biplanes and makeshift bombers, it stood out as a true strategic system. With its heavy payload, long range, and robust defense, the Muromets helped define the basic attributes of the heavy bomber class for the next generation of air warfare.

Final Missions: The Ilya Muromets in the Russian Civil War

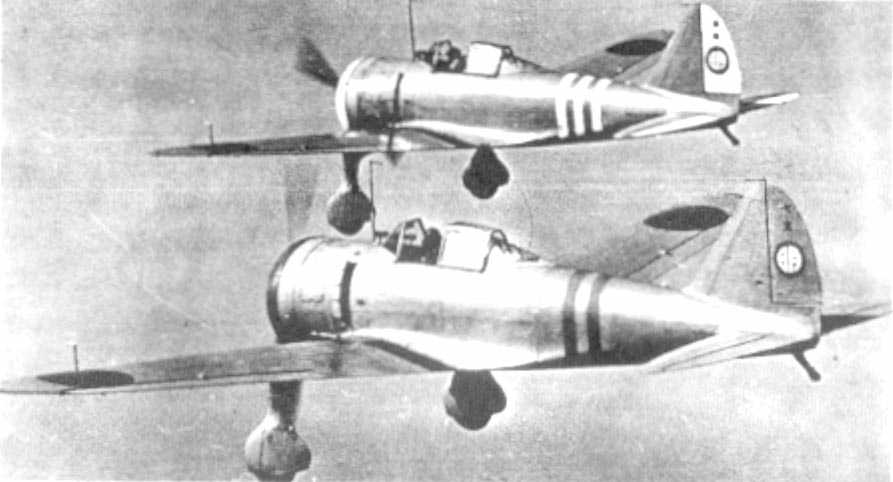

After the collapse of the Eastern Front and the Bolshevik seizure of power in late 1917, surviving Ilya Muromets aircraft came under the control of the nascent Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Air Fleet. Several aircraft remained airworthy in Petrograd and Moscow, operated by former Imperial crews who had aligned themselves with the new regime.

In early 1918, the Muromets were formally integrated into the Red Air Fleet. Their crews were reorganized into new detachments, sometimes led by elected commanders in keeping with early Soviet military practice. Maintenance, however, became a persistent challenge. A shortage of spare parts, experienced mechanics, and aviation fuel restricted flight readiness. Still, a limited number of sorties were flown in the early stages of the Russian Civil War.

Muromets aircraft saw action in southern Russia, particularly around Tsaritsyn (modern Volgograd) and in campaigns against White Army forces in Ukraine. Their operational utility was constrained by their size, complexity, and high maintenance requirements. Nevertheless, when employed, they conducted bombing raids, reconnaissance, and leaflet drops—serving as both tactical assets and psychological instruments.

One crew member, A.K. Petrenko, recounted a mission against White cavalry near the Don region in September 1919:

“The leaflets were dropped. Romanov turned the plane back, but suddenly another column of cavalry appeared on the ground. We still had four unused bombs; the appearance of the White cavalry column was very timely. But then something happened that made us seriously reconsider the tactics of bombing moving enemy units… We flew after the column and had almost caught up with it when, to our surprise, the cavalry showed no intention of scattering, as they usually did during air raids. Suddenly, the column turned around and galloped straight toward the aircraft. We didn’t have time to drop a single bomb—the cavalry had already raced beneath us. Romanov made a wide turn before we went back and caught up with the column again. The White Guards repeated their maneuver, but two of our bombs still fell at the rear of the column. Then, turning around, we flew at low altitude and strafed the cavalry with machine-gun fire.”

By 1920, the remaining Muromets aircraft were mostly retired. One or two were still flown on ceremonial occasions or used for training, but the pace of technological change had rendered the design obsolete. Yet in Soviet memory and propaganda, the Ilya Muromets retained its symbolic weight. As the world’s first operational strategic bomber, it remained a proud artifact of Russian innovation—honored less for its final missions than for the doctrine it helped to create.

Conclusion: Strategic Aviation’s First Giant

The Ilya Muromets was more than a technological achievement; it marked the birth of a new class of weapon. As the first aircraft purpose-built for long-range, heavy bombing, and the first to fly operational missions with a four-engine configuration, it demonstrated that size, range, and multi-crew coordination could be harnessed to strategic effect. In contrast to the improvised bombers of the era, often little more than scouts fitted with small payloads, the Muromets was designed from the outset to carry substantial ordnance over significant distances and return with its crew intact.

Its service on the Eastern Front proved that large aircraft could conduct regular, multi-hour sorties with onboard gunners, bomb bays, and in-flight engine maintenance. Though only around sixty were built, the Muromets flew more than 400 combat missions, many of them deep behind enemy lines. Remarkably, only one was confirmed lost to enemy fighters, highlighting the advantage provided by defensive firepower, altitude, and crew redundancy.

The innovations pioneered in the Ilya Muromets—enclosed fuselage design, integrated bomb release systems, multi-engine reliability, and coordinated defensive armament—prefigured the core attributes of strategic bombers deployed during the Second World War. Aircraft such as the Handley Page Halifax, the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, and the Avro Lancaster followed principles first tested over the Eastern Front in 1915.

What began as a flying salon for Russia’s elite became a prototype for the future of aerial warfare. The Ilya Muromets was not only the world’s first four-engine bomber; it was the conceptual blueprint for the strategic bomber as a military instrument. Its legacy is measured not only in missions flown, but in the evolution of airpower that followed.

Patrick Kinville writes about Russian and Soviet aviation history. This article is part of an ongoing project exploring early military airpower.